The long road to college from California’s small towns

The substitution went awry quickly. Jill McWilliams, a loftier school guidance advisor was trying to persuade a student and her mother that the bright, motivated senior should apply to college.

"The mom said to her daughter, 'What, you think you're better than us?' The girl started crying and said, 'No, I don't. I'chiliad sorry," recounted McWilliams at Anderson New Engineering Loftier School in rural Shasta County.

"This story isn't unique. That's all also often what we're facing up hither."

The girl did not go to college.

The long route to college from California's small towns [VIDEO]

"The long road to college from California's pocket-sized towns" tells the story of helping more students get college degrees in Shasta County in the state'due south northern region.

And she's not lonely: As enrollment in California'south public 4-year universities surges, one demographic group is notably under-represented on the state's public college campuses: Students who come from the vast, lightly populated rural communities stretching across the deserts, mountains and valleys from Oregon to the Mexico border.

While 8 out of 10 students from rural areas graduate from high school, many are not ready for college. It starts with a lack of higher preparation beginning in 9th grade. Fewer rural students — 28 percent, compared to 41 percent of students in urban areas — took the required coursework for admission to the University of California or California State Academy, according to an EdSource analysis of 2018-19 state information.

As rural areas grapple with poverty and other challenges, the futures of young people — and their communities — should not be limited past lack of educational opportunities, said Phil Halperin, executive director of California Education Partners, a nonprofit that helps districts fix their students for college.

In California, about 1 in 10 students — more than than half a million — live in rural areas.

"If California holds itself upwardly as a progressive, forward-thinking country, a leader in the 21st century economy, it's absolutely critical we exercise this," Halperin said, referring to efforts to boost college readiness in rural California. "We take the economic imperative, the societal imperative, the moral imperative to work on this."

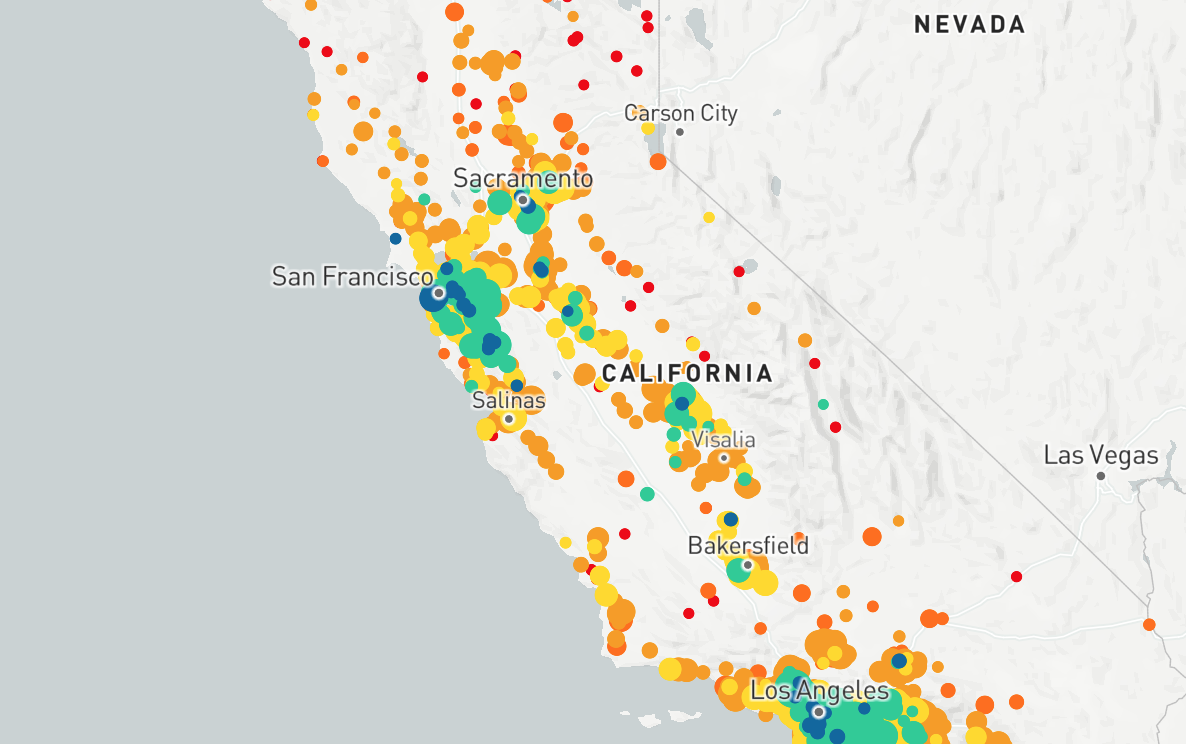

Interactive Map: Rate of high schoolhouse seniors enrolled in UC/CSU

View EdSource's interactive map showing how many seniors from each California high school enrolled in fall 2022 in the University of California or California Country University.

Starts in unproblematic school

Educators around the state have been working hard to reverse the trend, past boosting higher-prep classes in high schools and addressing the underlying factors that keep rural students from venturing to four-year universities.

The problem goes beyond filling out applications and submitting transcripts. It starts as far back as elementary school, when students commencement preparing for the high school courses they will need for college admission.

In loftier school, a lower share of rural students enroll in Advanced Placement classes for higher credit and fewer take the SAT or ACT standardized exam needed for freshman college admission.

That means that fewer rural students are able to boost their high school grade point average with their AP grades, which makes them less competitive in the admissions process. UC requires applicants to accept the Saturday or ACT; CSU requires virtually.

Julie Leopo / EdSource

Judy Flores, superintendent of the Shasta County Office of Education, says the drive to become students to college starts in Pre-K.

Some schools — including Anderson New Engineering High, where McWilliams works — are encouraging students to have the admissions tests, which for the offset time this year are beingness offered at the high school.

"The data was alarming. That'southward what brought us all together, saying, 'Nosotros've got to do something different,' " said Judy Flores, Shasta County superintendent. "And when we started looking at information technology, we quickly realized this isn't a high school problem. This is a Pre-G through 12th grade problem. Nosotros have to bring everyone together to work on this, or we're not going to change anything."

The root of problem, according to educators and policy experts, is nuanced and multi-tiered. In many rural communities, well-paying jobs that require available's degrees are scarce, and then students who desire to stay in the community have petty incentive to pursue higher education. And because attending a 4-twelvemonth-higher almost always means moving away, paying up of $12,000 a year to alive in a dorm, depending on its location, can seem daunting to low-income families.

Career and technical programs thriving

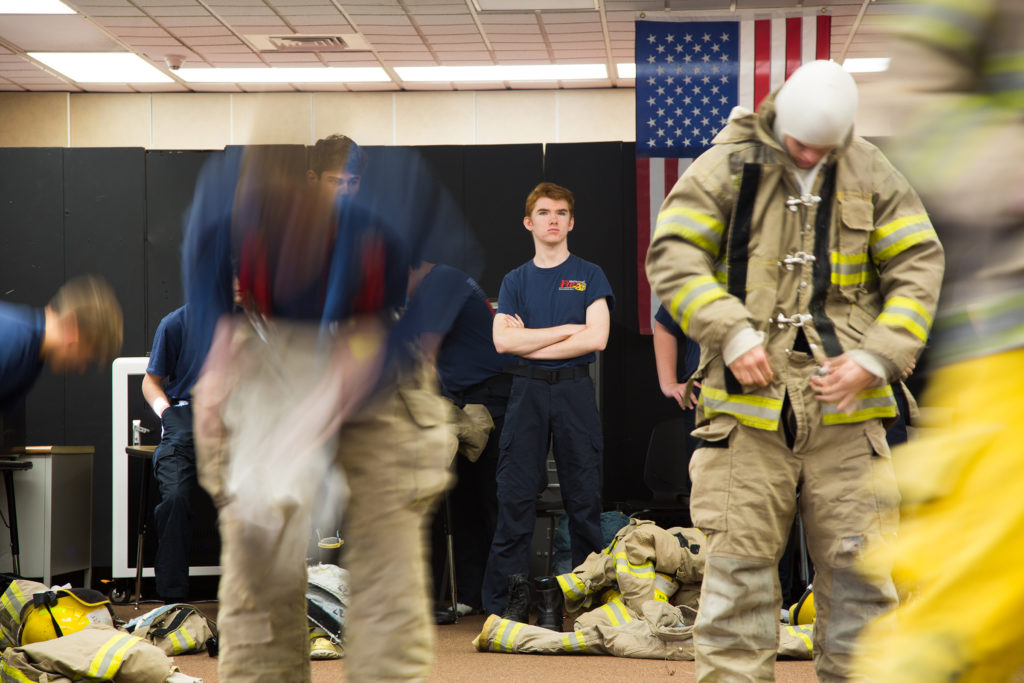

Career and technical courses offer many students in rural areas a pathway to careers that require minimal training later high schoolhouse. In Shasta Canton, Shasta Union Loftier School Commune offers 11 career training programs, including construction, medical technology, agronomics and law enforcement.

Among the most pop is the firefighter preparation programme, which has nearly 100 percent job placement later on graduation. Firefighting has a special entreatment to many Northern California students since the Carr Burn ravaged 230,000 acres in and effectually Redding in 2018, and the mortiferous Army camp Burn scorched Butte County the same twelvemonth.

"Nosotros know that not all our kids are going to higher. Merely we can lay a foundation, give them the hands-on experience, to be successful no matter what they decide to practice," said Milan Woollard, acquaintance superintendent of curriculum and educational activity. " CTE gives them a chance to accept what they've learned in the classroom and turn it into something tangible."

Most half the district's student body is enrolled in a career technical education program, Woollard said, just above the state average of 45 percent. Many students take these classes along with college prep classes, he said.

Many go to community college

Customs higher is likewise a success story in the region. Almost 45 percentage of high school graduates in Shasta, Tehama, Trinity, Modoc and Siskiyou counties go on to community college, mostly to Shasta Community College in Redding, according to college data.

But nigh students from rural areas who nourish customs colleges do not transfer to a college or academy, EdSource analysis reveals.

In Shasta County, relatively few — only 20 per centum — of Shasta College students become on to consummate bachelor's degrees. Many of those who practise get to four-year colleges tend to drop out for financial reasons, or they take trouble adjusting to crowded, diverse campuses or they lack encouragement from their families, said Becky Love, counseling coordinator at the Shasta County Function of Education.

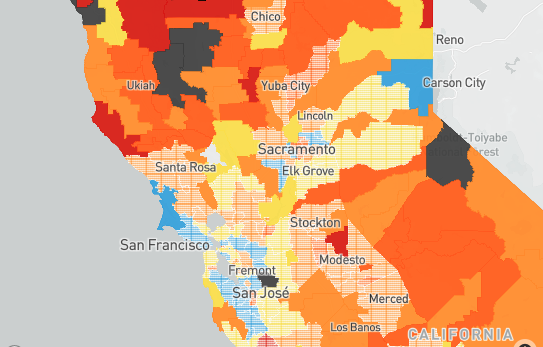

Interactive Map: Percentage of California students eligible for a four-yr country academy

Run across how many students in rural school districts took the courses required for access to the University of California or California State University.

'Nosotros need to look at the big picture.'

To boost the number of students who get to — and graduate from — four-year colleges, educators and community leaders in 5 northern counties have formed North State Together, an ambitious effort to promote college readiness. The three-twelvemonth-old project, funded by a $ten million grant from the McConnell Foundation, a Redding-based foundation that promotes education, health and environment, is aimed at encouraging young people of all ages to challenge themselves academically and earn college degrees.

The result, they said, could elevate the quality of life in the entire 20,000-square-mile region. And it's not just about encouraging students to take the Sat or Deed. The coalition is looking at the entire mindset: why more young people don't see college equally a adept option, and how that affects the unabridged customs, said Kevin O'Rorke, the coalition'due south director.

Rural California: An Pedagogy Separate

This article is part of an EdSource special report on the challenges facing schools and students in California's rural communities. Read about efforts in Shasta Canton and the San Joaquin Valley to get more students to seek bachelor's degrees and search a map to discover out what percentage of a high school's seniors authorize to enroll in UC/CSU.

Produced by EdSource: Carolyn Jones, reporter; Julie Leopo, lensman; Jennifer Molina, videographer; Yuxuan Xie, information visualization specialist; Daniel J. Willis, information analyst; Rose Ciotta, project editor; Denise Zapata, co-editor; Justin Allen, web designer; Andrew Reed, social media.

Shasta Canton has college rates of poverty, kid abuse, obesity and tobacco use, children in foster care, domestic violence and drug corruption than the rest of California, according to the county's demographic survey.

"Nosotros realized that the trouble is then circuitous, we really need to start thinking virtually it differently," O'Rorke said. "Maybe we need to look at the big picture, find out why we accept all these other problems — high rates of incarceration, habit, sexual attack, domestic violence. We need to be investing upriver. Rather than pulling someone out of the water and resuscitating them, how about nosotros non permit them fall into the h2o in the first place."

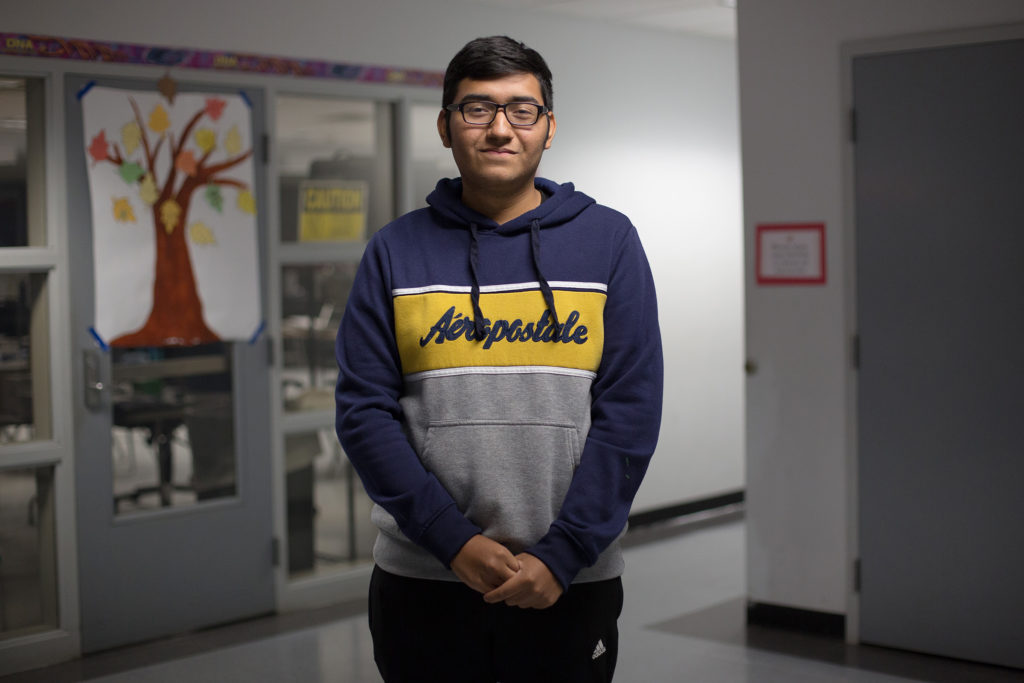

In Shasta Canton, the North Country Together initiative has paid off for Emiliano Alanis, a senior at Anderson New Technology High School who applied to four UC schools this fall. The son of Mexican immigrants, he and his sisters are the first members of the family to go beyond 6th grade. Emiliano'southward dream is to go to UC Irvine and enroll in its math teacher educational activity program.

Still, he'southward nervous about leaving Anderson, and its population of about 10,000. Aside from a few trips to Mexico to visit family and a college tour to Portland, he hasn't seen much of the world across Shasta Canton.

"But my mom's always pushed me to become to college, to have the life she never got to have," he said, adding that his mother, who is unmarried, works as a housekeeper to support the family of five. "And so I've tried to study hard and maintain my grades."

Some students are happy to skip college and go directly from high school to career. Arys Hardee, a classmate of Emiliano's, plans to get a firefighting job after graduation. In some ways, she says, her CTE firefighting classes are equivalent to higher. She's learning responsibleness and a range of skills, meeting new people and volition be eligible for a rewarding, stable job after she graduates high school.

Others opt to become directly to work.

Thirty miles south of Redding in Blood-red Bluff, Morgan Snively, who graduated a few years ago from Red Bluff High said he had a groovy education and had planned to pursue a career in carpentry, inspired past the schoolhouse's woodshop program. But a bicycle injury after graduation quashed his program to apprentice every bit a chiffonier maker. Instead he got a chore managing a smoke shop on Main Street.

"For how small-scale our town is, I feel our high school is pretty adept," he said. "But no, I don't desire to become to higher. I'1000 doing this instead. This is good."

Higher initiatives tailored to each community

Each canton and school in the North Country Together region is undertaking its own initiatives, based on local needs. Trinity County is tackling kindergarten readiness by working with parents of young children to ensure they're receiving any services they need, and know what their children need to exist set for school. Modoc Canton has fix upwards internships with local businesses for every loftier school student. In many districts, high school counselors now go direct to classrooms to talk to students about college entrance requirements, financial aid and career planning, instead of waiting for motivated students to drib in during office hours. High schools have besides changed their graduation requirements to include more college-prep classes, adding additional math and science requirements.

At Shasta College, expanded counseling services helps ensure students are taking the right courses to transfer to a UC or CSU. The college has as well opened classrooms with Cyberspace access in remote towns such as Weaverville, so students in areas with limited Internet access tin can accept online courses.

Results have been promising and so far. In 2011, Shasta College graduated 350 students with certificates or associate degrees. By 2022 that number had more than than doubled, and half of the students graduated with honors.

San Joaquin Valley students set their sights on college

Find out how some San Joaquin Valley schools accept made college prep a priority.

Those that finished two-yr vocational document programs also had positive results. Nearly all students in the wellness and data applied science fields establish jobs locally afterward graduating, and more than than 70 percent of all other fields, including agriculture and business organisation management, found nearby piece of work in their chosen field.

Improving pedagogy outcomes doesn't merely benefit individual students, said Sue Huizinga, a student support managing director at Shasta Higher. It can lift an unabridged family and, over time, transform the community.

"For me, it'due south about opportunity," said Huizinga, her eyes filling with tears as she spoke. Huizinga works in the local function of the federal TRIO program, which helps low-income students with college readiness.

"I want every young person to have the opportunity to provide for themselves and their families, to get the all-time education they can, to live good, happy, healthy lives," she said. "If they're non getting those opportunities, we need to practise everything possible to give it to them."

O'Rorke said the message is commencement to sink in, even at the uncomplicated schools.

"We have ane schoolhouse where they now enquire parents on registration twenty-four hours where they want to transport their kids to college. Not if, simply where," he said. "I was stunned when I heard that. That'south so absurd."

Meanwhile, in Anderson, McWilliams said she'due south confident the North State Together efforts will modify the college-going civilization in her hometown. The stakes are too loftier to fail, she said.

"This is about admission and equity for all. I believe that with all my eye," she said. "Instruction is the not bad equalizer. I don't care who you lot are or where you lot came from, you deserve a chance to get an education."

To get more than reports similar this one, click here to sign upward for EdSource's no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Source: https://edsource.org/2019/the-long-road-to-college-from-californias-small-towns/621428

0 Response to "The long road to college from California’s small towns"

Post a Comment